Dr. R. Bruce Winders, Former Alamo Director of History and Curator

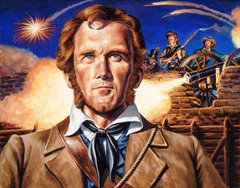

One name forever linked to the Battle of the Alamo is James Bowie. Although not yet a household name like “Crockett” at the time of the battle, Bowie and his exploits had gained renown in some quarters. His death on March 6, 1836, however, ensured his place in history as one of Texas’ most interesting figures.

Many early Americans were drawn to the western frontier of the new republic — among them the Bowies. James’ parents had lived in Tennessee before moving to Kentucky, where James was born 1796. On the move again in 1800, the family crossed the Mississippi River into Missouri and settled in what was then Spanish Louisiana. Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, the Bowies moved once more, this time to southeastern Louisiana. Not yet a state, Louisiana still retained a frontier atmosphere.

James soon struck out on his own, intent on making his mark on the world. In the antebellum South, two commodities could lead to wealth and respectability — land and slaves. James Bowie speculated in both. Before long he had acquired title to thousands of acres throughout Louisiana and Arkansas Territory. High-stakes speculating was a risky business and while amassing a small fortune, Bowie was also making enemies. In 1826, Bowie was shot and wounded by a rival in the lobby of an Alexandria hotel, an event that proved to be a turning point for him.

James and his older brother, Rezin, shared an extremely close relationship. Concerned for his brother’s safety, Rezin gave James a long-bladed butcher knife. The “Bowie Knife”, as it came to be called, gained its reputation the following year in the hands of James near Natchez in an incident known as the Sand Bar Fight. Although shot twice and stabbed several times, James was still able to fend off his attackers. The incident made both the man and the knife legends as word of the deadly fight spread. Demand for the “Bowie Knife” grew as others wanted to own such a formidable weapon.

James Bowie immigrated to Texas in 1830 after U.S. officials determined that many of his land claims were rooted in fraud. A charming and energetic man in his mid-thirties, Bowie visited San Antonio de Béxar where he met Ursula de Veramendi, the daughter of Juan Martín de Veramendi, vice governor of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas. James and Ursula were married in 1831. Thus, Bowie had allied himself to one of the most powerful families in Texas and with the Tejano community. Tragically, his young wife and her parents died in Monclova in 1833 when a cholera epidemic swept across northern Mexico.