The Battle swiftly became a distant chapter in the history of San Antonio. A new era had begun: one of statehood and then U.S. Army occupation at the Alamo.

Desolate Ruin to Busy Staging Post

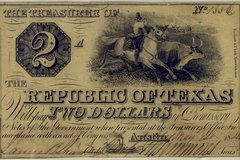

The Republic of Texas (1836 – 1846)

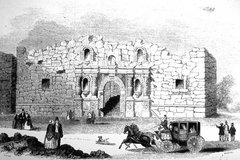

During the Republic period, the Alamo was largely forgotten. The once proud stand for independence was no longer fresh in people’s minds. Much of the outer walls of the compound were torn down and the building fell into further disrepair. Inhabitants of the new Republic of Texas were rebuilding and moving on from the turmoil of the Revolution. Their concern was to regain some kind of normalcy in a world that still had political unrest and frequent interactions with combative indigenous tribes. Although there were moments of remembrance, the Alamo would not be part of the daily lives in San Antonio again until after U.S. statehood in 1845.

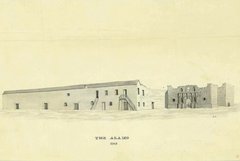

Seth Eastman

The Alamo, 1848

Watercolor on paper

Collection of the McNay Art Museum, Gift of Robert L. B. Tobin in memory of Madeline and John W. Todd

Annexation: Texas Becomes an American State

Occupation of Alamo Plaza by the U.S. Army took place shortly before statehood, when Companies A and G of the United States Army’s Second Dragoons marched from Fort Washita, Arkansas, to San Antonio, arriving in October 1845.

Formal documents that would secure Texas as the 28th state in the Union would not be signed for several more months. The official transfer of power from “Nation” to “State” took place in Austin on February 16, 1846, when Anson Jones, the last President of the Republic of Texas, gave his farewell speech.

The city of San Antonio swiftly acted in designating plots of land to establish a permanent base of operations for the Army. By February 4, 1846, the San Antonio Mayor and Board of Aldermen authorized Colonel Harney, Commander of U.S. forces, to take full possession of 100 acres of land. Although the U.S. military was given land, it still needed structures to house troops and supplies. By early 1846, war with Mexico was imminent and the need for a staging post for troops and supplies was apparent. The U.S. Quartermaster entered into lease agreements with the City and the Archdiocese of San Antonio to utilize the abandoned Alamo structures: the Church and Long Barrack. The Alamo would once again be occupied by military forces in preparation for a new fight with Mexico.

The Mexican-American War (1846 – 1848)

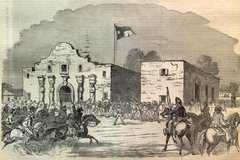

Throughout the life of the Republic and during the early years of statehood, there were constant skirmishes along the Texas-Mexico border due to misconceptions of where the border was. These border disputes eventually led to full-scale war between the United States and Mexico. The Mexican-American War lasted nearly two years and inflicted heavy casualties on both sides. The Alamo and San Antonio would play a vital part in the war effort, functioning as a staging point for supplies and men to aide in the war effort. The Alamo became a bustling supply hub that would set the stage for more adaptive use in the future. The Long Barrack was used as offices and quarters, whereas the Church was roofed and had a second floor constructed. The Church was used to house supplies. On February 2, 1848, the Mexican government signed the Guadalupe Hidalgo Treaty, bringing an end to the Mexican- American War. Soon after, the Alamo resumed its role as a staging point for the military and large groups of settlers migrating west.

How the U.S. Army Changed the Alamo

Once the U.S. Quartermaster took control of the remaining Alamo grounds, much work was needed to restore the structures to working order. The Long Barrack was repaired, with walls fixed and new plaster applied. In some cases, new windows and doorways were added to the structure. Photographs and drawings of this time show a staircase on the exterior of the southern end of the building. The Long Barrack was used as officer quarters and offices, as well as workshops.

The Alamo Church needed substantially more work to make it functional for the Quartermaster. At the time the U.S. Army arrived, the earthen rampart constructed during the fortress period was still present. The diary of Edward Everett details the removal of the rampart, as well as clearing out of the other rooms within the Church. Once the Church interior was cleared, a roof was added to the structure. The wooden gable roof built by the U.S. Army was the first roof that the Church had possessed in all its years of existence. Never finished during the mission period, the structure took on a much different look. The last major change that the U.S. Quartermaster ordered was the construction of the parapet, which gives the Alamo Church its iconic silhouette that is today recognizable throughout the world.

The American Civil War (1861 – 1865)

With the election of 1860, Abraham Lincoln became the 16th President of the United States, forever changing American history. A new war was brewing: the American Civil War caused a great divide throughout the country, forcing friends, family, and neighbors to choose a side. The Federal Government, or Union, fought bloody battles with the Confederate, or Southern states. Texas signed the Ordinance of Secession on February 1, 1861, and was admitted into the Confederacy on March 23, 1861. Texas’s shipping ports, agriculture, and livestock were the lifeblood of the Confederacy. The Alamo was cast into the national spotlight when Texas Confederates seized all Federal property in Texas, including the Alamo Quartermaster Depot. Little is known about the use of the Alamo during this period. The war raged throughout the North and the South. Over 70,000 Texans fought in the Civil War, and 20,000 would never see Texas again.

Return of the U.S. Army

When the Civil War ended in April of 1865, Union soldiers once again occupied San Antonio and the Alamo. While the city and the buildings in Alamo Plaza changed throughout 1845-1865, the necessity of supply and demand did not. The population was growing and the need for material and supplies was growing with it.

In 1861, disaster struck when fire ravaged the Alamo Church’s interior. As a result, other structures in Alamo Plaza and the surrounding areas had to be used to house the Army’s supplies. For nearly ten years the Army used Alamo Plaza as their main hub to transfer goods throughout Texas and the western United States.

U.S. Army Leaves the Alamo for Fort Sam Houston

During this time period of the U.S. military occupation in San Antonio, one of the biggest complaints was the fact that the Army did not have a centralized location. Warehouses, offices, and quarters were spread throughout the city, oftentimes in buildings that were leased. It was often argued that the U.S. military could cut costs and work more efficiently if these locations were consolidated.

In 1875, command of the district of Texas was given to General E. O. C. Ord. Under Ord’s supervision, and funding was allocated to build a permanent garrison, which would come to be called Ft. Sam Houston. The need for military storage in Alamo Plaza was no more and meant that the surrounding buildings were available for commercial use. Although removed from the Alamo grounds, the United States Army would establish a lasting relationship with San Antonio and the Alamo.