After several years of petitioning the Viceroy of New Spain, Baltasar de Zúñiga y Guzmán, Fray Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares was granted permission to establish a mission at the location of the San Antonio River, which Olivares had observed during an expedition in 1709. On May 1, 1718, Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares performed the rites and rituals establishing Mission San Antonio de Valero west of San Pedro Springs, located just a few miles from the headwaters of the San Antonio River. The mission was founded as a Spanish foothold in a territory that Spain rarely entered, with the intent to convert indigenous peoples to Catholicism and instruct them to become Spanish citizens. With the establishment of Mission Valero, the associated villa and presidio were also founded along San Pedro Creek by Martín de Alarcón on May 5, 1718.

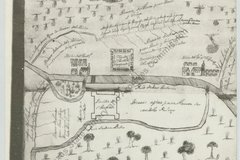

Image (above): Detail of a 1764 map of the San Antonio Missions, created by Luis Antonio Menchaca, JCB Map Collection, John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.