By: Dr. Bruce Winders, Former Alamo Director of History and Curation

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase had left the border between Texas and Louisiana undefined. Based on previous French claims to Texas, many people in the Unites States believed that Louisiana stretched all the way to the Rio Grande. Beginning in 1810, Mexico’s war for independence created a chaotic situation that enabled large military expeditions of Mexican revolutionaries and American volunteers to capture Nacogdoches, La Bahía, and even San Antonio de Béxar.

Although Spanish royalists eventually defeated several attempts to overthrow the King’s rule and replace it with a republic, the effort to defend Texas took a significant toll on its inhabitants. Several hundred residents in San Antonio were either executed or forced to flee to Louisiana for siding against the government. The war also had upset the system of annual gifts to Indians which had cut down on the number of raids. As a result, raiding increased in the years prior to Mexican independence.

The effects of Mexico’s war of independence were felt in San Antonio de Béxar. On January 11, 1811, nearly five months after Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla’s “Grito de Dolores” sparked revolt against the Spanish royal government, a retired militia captain in San Antonio issued his own call for revolution. Juan Bautista de la Casas and his followers arrested Spanish officials and began confiscating their property. Lacking the support of local leaders, his revolt failed, and he paid for his actions with his life. The captain’s head was placed on a pole and left in Military Plaza as a reminder of the fate that awaited those who challenged royal authority.

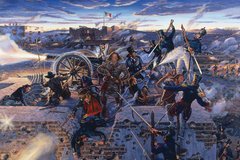

In late 1812, an army of three hundred or more Mexican revolutionaries and American volunteers entered Texas and captured Nacogdoches. Governor Manuel María de Salcedo amassed several hundred Spanish soldiers and laid siege to La Presidio La Bahía, which had been seized by members of the Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition. In February 1813, Salcedo broke off the siege and withdrew to San Antonio. On March 29, the filibuster expedition defeated royalist forces nine miles southeast of San Antonio at the Battle of Rosillo. On April 1, the insurgent army, which had grown to more than eight hundred, entered San Antonio. On April 6, its leaders declared independence from Spain. The new republic was represented by a green flag.

In response to these events, the commandant of the Internal Provinces, General Joaquin de Arredondo, sent a vanguard into Texas in preparation of a campaign to reclaim the province. The rebels defeated Colonel Ignacio Elizondo outside San Antonio at the Battle of Alazán Heights on June 20, 1813. Nevertheless, Arredondo continued to march towards Texas, collecting men and supplies and stopping to train his recruits along the way. On August 18, 1813, the royalist and republicans clashed twenty miles southwest of San Antonio at the Battle of Medina. Arredondo’s army crushed the republicans, executing and pursuing rebels even to the Louisiana border.

Arredondo occupied San Antonio for nearly a year following his victory on the Medina River. He continued to execute rebels, confiscate property, and imprison the women of San Antonio, who were forced to cook for his soldiers. During this time, some prisoners were held at the Alamo. Other expeditions were attempted but none were as serious as what occurred in 1812–1813. Their cumulative effects depopulated Texas and left it in economic disarray. Moreover, the drastic decline in population set the stage for the opening of Texas to foreign immigrants as a way to repopulate the region and hopefully create conditions where the region could prosper.