Dr. R. Bruce Winders, Former Alamo Director of History and Curator

The telling of the 1832 disturbance at Anahuac usually revolves around strong two personalities: Juan Davis Bradburn and William B. Travis. The former was a Kentuckian in the service of the Mexican government and the later was a native of South Carolina who had recently immigrated to Texas from Alabama. Bradburn, a colonel in the Mexican Army in command of the Fort Anahuac located near Galveston Bay, used his power to harass the colonists by interfering with their trade and right to self-government. Travis, a young lawyer incurred Bradburn’s wrath challenging by the colonel’s authority. The clash between the two men could have easily become a major revolt if Mexican officials had not intervened on the behalf of the colonists and removed Bradburn from command, ordering the chastened officer back to Mexico. In this traditional interpretation of the clash, the colonists had stood up to a petty tyrant and won.

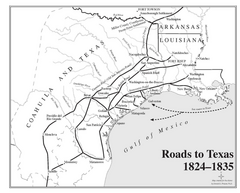

As in most historical incidents, the events that occurred in June 1832 were more complex than the above explanation. By 1830, officials had determined that the policies enacted to regulate the flow of Americans into Mexico were not being enforced. While some empresarios such as Stephen F. Austin attempted to screen those arriving to make sure they would become responsible and law-abiding colonists, other contractors did not. Making the situation even worse, an increasing number of Americans had begun to arrive uninvited on their own, lured by rumors of free land. Even more troubling and in defiance of Mexican law, colonists were settling along the gulf coast, which enabled them to carry on a lucrative illicit trade with New Orleans. Officials in Mexico City realized that Texas was in danger of becoming Americanized. If the trend continued, what would stop these foreigners who appeared to not value Mexican citizenship and the other benefits given to them from attempting to reunite with the country of their birth and taking Texas with them?

Mexico’s concern over the Texas resulted in the Law of April 6, 1830. The decree closed Texas to immigration by Americans. Instead, Mexican families were encouraged to move to Texas from other states within the federal republic. Troops were sent to Texas with orders to build additional forts to provide a visible government presence. These soldiers would help intercept smuggled goods coming from the coast and across the Louisiana border. Moreover, the seven year grace period on no taxes on trade extended to colonists was coming to an end and arrangements were made for the establishment of custom houses and tax agents. These and other steps were intended to reassert the government’s control over Texas.

Mexico’s ongoing internal political struggle between the states’ rights oriented Federalist and the nationalistic Centralists touched even the Department of Texas, then part of the state of Coahuila y Tejas. Although the national government had laid out the basic framework of colonization, it left it to the individual states to determine their own laws on immigration. A state official, José Francisco Madero, arrived in 1831 to issue land titles to Austin’s colonists. He also authorized the founding of small settlement called Liberty, located on Trinity River several miles above its mouth. Colonel Bradburn, acting as an agent of the Centralist administration then in power, voided Madero’s actions, claiming that the recent national Law of April 6 superseded state law. Later that year, George Fisher, a Hungarian in the service of the national government, arrived to assist Bradburn in regulating trade and collecting taxes. Resentment against these officials grew among the colonists who viewed the new rules enforced in part by convict-soldiers assigned to Bradburn, as examples of tyranny. Although Austin repeatedly warned the colonists not to take part in Mexico’s internal political struggles, their republican upbringing caused many of them to naturally side with the Federalists and their stance on state’s rights.

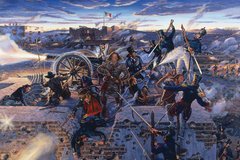

In June 1832, the situation on the gulf erupted. The catalyst was Bradburn’s arrest of two local attorneys, Patrick Jack and William Barret Travis. With no jail at hand, the colonel had his prisoners placed in a large brick kiln inside Fort Anahuac. Local civil authorities demanded the men’s release and even captured nineteen Mexican soldiers to hold as hostages until Bradburn met their demands. Although face-to-face meetings between Bradburn and the colonists failed to break the stalemate, the time spent talking allowed both sides send for help. Colonists in the gulf coast region vowed to use force if necessary. On June 26, 1832, an engagement occurred between the Mexican garrison at Fort Velasco, located near the mouth of the Brazos River, and Texan reinforcements on their way to Anahuac. Known as the Battle of Velasco, the combined casualties from the fight totaled 12 killed and 30 wounded, with losses roughly equal on each side. Outnumbered and surrounded, however, Col. Domingo de Ugartechea surrendered the fort. Additional bloodshed was prevented by the arrival of Col. José de las Piedras from Nacogdoches, who removed Bradburn from command and released Jack and Travis.